MARKET UPDATE - Is A 1970s-Style Resurgence In Inflation Coming?

Please note that this is a free article of High Yield Landlord. If you find it valuable, consider joining our service for a 2-week free trial. You'll gain immediate access to my entire REIT portfolio, real-time trade alerts, exclusive REIT CEO interviews, and much more.

MARKET UPDATE - Is A 1970s-Style Resurgence In Inflation Coming?

As the Federal Reserve begins to turn dovish on monetary policy, is the United States economy at risk of a resurgence in inflation akin to what was experienced in the 1970s?

Some pundits in the financial media fear that a Fed pivot toward easing in 2024 would repeat a similar mistake as was made in the 1970s.

The narrative goes that as inflation receded from its peak in 1974, the Fed pivoted toward easing too soon, which allowed inflation to make a resurgence in the second half of the decade.

Is this narrative accurate? Is the US bound to have a resurgence in inflation in 2025 and beyond if the Fed pivots to easing in 2024?

In short, our answer is no. We think this narrative is inaccurate. While there is one important similarity between the experience of COVID-19 and the 1970s inflationary bout, there are many significant differences between then and now.

We'll cover these differences below and explain why we do not believe the US is headed for an inflationary resurgence, whether or not the Fed goes through with a dovish pivot.

A Brief (And Hopefully Painless) Explainer of Monetary Policy & Inflation

Central bank monetary policies are not the primary factor that determines inflation. They aren't today, and they weren't back in the 1970s either.

That is because central banks don't actually print money in the sense of creating dollars that go directly into the money supply. They adjust the flow of bank reserves, which should eventually lead to corresponding changes in bank lending, which in turn should eventually cause changes in the supply of money circulating around the economy.

All else being equal, a loosening of monetary policy should catalyze increased bank lending at lower interest rates, as well as reduce yields on savings vehicles that encourage savers to seek out higher yields in riskier assets such as bonds, stocks, and real estate. This is how increased bank lending typically produces an increase in the money supply.

This is generally a healthy way to grow the money supply, because the increased bank lending theoretically stimulates a corresponding increase in production. Supply grows along with demand, and inflation generally remains muted as a result.

So where does inflation come from then?

Unsurprisingly, it can come from two angles: the supply side or the demand side (or both).

Supply-side inflation results from some sort of shock that significantly reduces the supply of goods and/or services while demand remains more or less stable.

Demand-side inflation results from a surge in the money supply (and thus consumer spending power) that is not accompanied by a corresponding increase in production.

COVID-19 was a uniquely perfect storm in the sense that we had inflationary pressure from both the supply and demand sides. Production fell, supply chains broke, and on top of that, the federal government printed trillions of dollars to pump directly into the economy, immediately boosting consumer spending power.

The Federal Reserve wasn't behind either of these inflationary drivers.

But (and this is very important) the Fed played a major role in facilitating and enabling the federal government's fiscal largesse by massively increasing the Fed's balance sheet concurrently with the government's debt issuance.

Effectively, the Fed acted in concert with, rather than independently from, the government's fiscal spending.

This hand-in-glove cooperation between fiscal and monetary policymakers is dangerous precisely because of the risk that it will lead to short-termist, politically motivated policy decisions. This is why the Federal Reserve was conceived and mandated to be independent of politics.

The 1970s Example

We saw a similar breakdown in that barrier of Federal Reserve independence in the 1970s.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the Federal Reserve was helmed by William McChesney Martin, the longest running chairman of the Fed who served under 5 different presidential administrations. Back then, the Fed didn't have today's famous "dual mandate" of low inflation and low unemployment. Martin's goals of low inflation and economic stability were generally achieved during this two-decade period.

Martin was also a staunch guardian of the Fed's independence. It was Martin who originally said that it is the Fed's job "to take away the punch bowl as the party gets going." His well-known and publicly stated opinion was that the Fed answers to Congress, not the president.

This didn't sit well with Richard Nixon, who became President in 1969. Back in 1960, when sitting vice-president Nixon first ran for president, Martin's Fed was engaged in tightening monetary policy, which Nixon blamed on his defeat against John F. Kennedy.

Nixon wanted a more pliable Fed chairman who would provide loose monetary policy during his first term (especially in the run up to Nixon's 1972 reelection), so he pressured Martin to resign immediately. Martin refused, so in 1969, Nixon appointed Arthur Burns as a special advisor until Burns could be installed as the Fed chairman in 1970. Burns proved to be a far more compliant central banker than Martin, which is exactly why Nixon appointed him.

Federal government spending and the money supply predictably grew during Nixon's first term, while the Fed Funds Rate fell during the 1970 recession and remained fixed at a lower rate through 1971 and 1972.

Economists widely agree that this breakdown in Fed independence played a major role in inciting the inflationary uptrend that continued through the 1970s.

Of course, other factors were also at play.

The Vietnam War draft removed about 2 million people from the workforce in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

The labor force was heavily unionized back then, which helped a wage-price spiral take effect.

Welfare programs were expanding rapidly.

The US was more dependent on foreign nations for its oil supply, which led oil embargoes to incite a greater contagion effect on other prices.

A huge wave of Baby Boomers were reaching their prime spending years throughout the 1970s.

All of these factors played a role in the decade's high inflation, but it is important to remember that each of the big spikes in inflation during the 1970s was preceded by a corresponding spike in money supply growth in the years prior.

Federal policies like rapidly expanding welfare programs and price controls created the conditions for an inflationary surge, but huge money supply growth strongly fueled the fire.

The Present Situation

We saw a very similar situation play out during and after COVID-19.

Government stimulus spending, facilitated by ultra-easy monetary policy and Fed balance sheet expansion, caused a massive spike in the money supply in 2020 and 2021 that subsequently led to a surge in inflation in 2021 and 2022.

So far, however, there has been no resurgence in the growth of the money supply.

In fact, for the entirety of 2023, the money supply experienced a rare contraction. This is very different than the 1970s, during which money supply growth never dipped into negative territory. During that decade, growth in the money supply made higher lows on each swing.

Could there be another surge in the money supply in the coming years? It's possible. But what would cause it?

COVID-19 was a rare case of Congress coming together with the president to enact massive fiscal spending. But at this point, Congress appears to be far too divided to push through any more big spending packages, especially the kind that put dollars directly into the hands of consumers. Even if there was another pandemic, it seems unlikely that the government would engage in quite the same degree of largesse as was seen in 2020 and 2021.

Meanwhile, the other economic factors that contributed to elevated inflation in the 1970s are also not at play in today's economy.

Unionization today is far lower than the 1970s: 11% in 2022, compared to about 25% during the 1970s. Likewise, there is no war draft in the US pulling millions of workers out of the labor force.

In fact, the labor force participation rate for prime-aged workers is currently near its highest level since 2002.

Ask anyone in virtually any industry, and they'll tell you that the labor shortage is not nearly as pronounced today as it was a year or two ago. The labor market is much healthier today than then.

Job openings are quickly receding back toward pre-pandemic levels, and the total US nonfarm labor force numbers 5 million more workers today than immediately preceding COVID-19.

This signifies that the shock to the US labor market was a one-time event, not terribly reminiscent to the 1970s.

What about wage growth?

In the 1970s, we saw a clear pattern play out three times: first, the money supply surged, then wages followed, and finally inflation spiked after that.

In the COVID situation, we saw US wage growth spike and peak concurrently with CPI inflation.

While it is impossible to say with certainty where wage growth will go from here, it certainly appears as though the trajectory will continue downward back toward pre-COVID levels of around 3-4%.

Another major difference between today and the 1970s is the fact that the US is mostly energy independent.

Back in the 1970s, the US struggled to increase both oil and gas production. The country was far more dependent on foreign producers back then.

This situation only worsened through the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, until the fracking revolution began after the Great Recession of 2008-2009, leading to a major boom in US oil & gas production. Both are now hitting all-time highs.

Today, the US is becoming the world's supplier of oil & gas, a very different situation than that of the 1970s.

Now, what about demographics?

Today, the Millennial generation are in their prime consumption years, and Gen Zers are early in their careers. Could this be a catalyst for sustained inflation?

Probably not. At least, not to the same degree as the 1970s.

Millennials are straddled with far more student debt than Boomers ever were, and they mostly entered the workforce in the weak economy following the Great Recession. As the least experienced workers following that major recession, Millennials saw the quickest rebound in employment but the slowest rebound in earnings compared to older generations of workers.

As such, Millennials simply have far less spending power than their parents' generation did at the same age.

Gen Zers aren't much better off. According to a 2022 study by Consumer Affairs, Gen Zers early in their careers have an astounding 86% lower real purchasing power than Baby Boomers did at the same age.

Prices have skyrocketed in the intervening 5 decades. For example, median rent today is $2,000, compared to $800 in inflation-adjusted dollars during the 1970s.

Millennials and Gen Zers, on the whole, have nowhere near the real spending power that their parents' generations did. Thus, a demographically driven increase in structural inflation does not look probable.

Finally, consider another major difference between the 1970s and today. Back then, the US welfare state was in its early stages and expanding rapidly. These welfare programs basically redistributed money from higher-income households with a lower propensity to spend to lower-income households with a higher propensity to spend, thereby increasing consumer demand for certain products and fueling overall inflation.

From 1965 through 1981, transfer payments for social benefits increased 2.5x faster than GDP.

Compare that to the last 5 years. Certainly, the spikes in transfer payments during COVID were huge as the federal government boosted unemployment benefits and distributed stimulus checks, but overall, the growth in transfer payments for social benefits has not been much higher than GDP in the last 5 years.

Whatever degree to which the rise of the welfare state helped to fuel inflation in the 1970s, that does not appear to be at play -- or even plausibly repeatable -- today.

Back To Our Macro Thesis

Our thesis for a long time now has been that the fiscal, monetary, and economic circumstances surrounding COVID-19 represented a one-time, idiosyncratic event, not the beginning of a new secular inflationary environment similar to the 1970s.

Our recent experience does have one important thing in common with the 1970s: In both cases, the inciting event was a close collaboration between fiscal and monetary policymakers. That is, in both cases, large increases in government spending were facilitated by the Fed's easy money policies.

Other than that, today's situation bears very little resemblance to the 1970s.

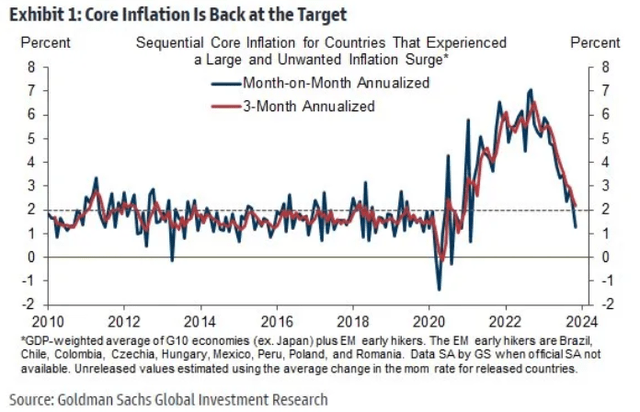

Already, real-time inflation across the world is already back under the common 2% target.

And when it comes to the US specifically, there are no leading economic indicators signaling an impending resurgence in activity or consumer demand.

In fact, in The Conference Board's November reading, every leading economic indicator except stock prices were flat or negative.

With supply chains restored, production levels back at all-time highs, labor markets looking healthy, wage growth easing, COVID-era savings depleted, and extraordinary fiscal stimulus measures now firmly in the rearview mirror, we continue to see signs that the US economy is returning to its pre-COVID status of low inflation and low growth. We believe interest rates will follow in 2024 by dropping as well.

Once again, we conclude that this is a marvelous environment for commercial real estate, especially beaten-down REITs.

We believe the outperformance we saw from REITs in the final two months of 2023 should continue over the course of 2024.

Finally, please note that this is a free article from High Yield Landlord. If you found it valuable, consider joining our service for a 2-week free trial. You'll gain immediate access to my entire REIT portfolio, real-time trade alerts, exclusive REIT CEO interviews, and much more. We are the largest and highest-rated REIT investment newsletter online, with over 2,000 paid members and more than 500 five-star reviews.

We spend 1000s of hours and over $100,000 per year researching the market for the most profitable investment opportunities and share the results with you at a tiny fraction of the cost.

Get started today - the first 2 weeks are on us:

Sincerely,

Jussi Askola & Austin Rogers

Analyst's Disclosure: I/we have a beneficial long position in the shares of all companies held in the CORE PORTFOLIO, RETIREMENT PORTFOLIO, and INTERNATIONAL PORTFOLIO either through stock ownership, options, or other derivatives. High Yield Landlord® ('HYL') is managed by Leonberg Research, a subsidiary of Leonberg Capital. All rights are reserved. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment is suitable for a particular investor. The newsletter is impersonal and subscribers/readers should not make any investment decision without conducting their own due diligence, and consulting their financial advisor about their specific situation. The information is obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but its accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The opinions expressed are those of the publisher and are subject to change without notice. We are a team of five analysts, each contributing distinct perspectives. Nonetheless, Jussi Askola, the leader of the service, is responsible for making the final investment decisions and overseeing the portfolio. We do not always agree with each other and an investment by Jussi should not be taken as an endorsement by other authors. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Our portfolio performance data is provided by Interactive Brokers and believed to be accurate but its accuracy has not been audited and cannot be guaranteed. Our portfolio may not be perfectly comparable to the relevant index. It is more concentrated and may at times use margin and/or invest in companies that are not typically included in REIT indexes. Finally, High Yield Landlord is not a licensed securities dealer, broker, US investment adviser, or investment bank. We simply share research on the REIT sector.