MARKET UPDATE - Population Bomb, Defused: The Underappreciated Impact Of Peak Humans

We are in the midst of a new and truly unprecedented shift in the trajectory of human history.

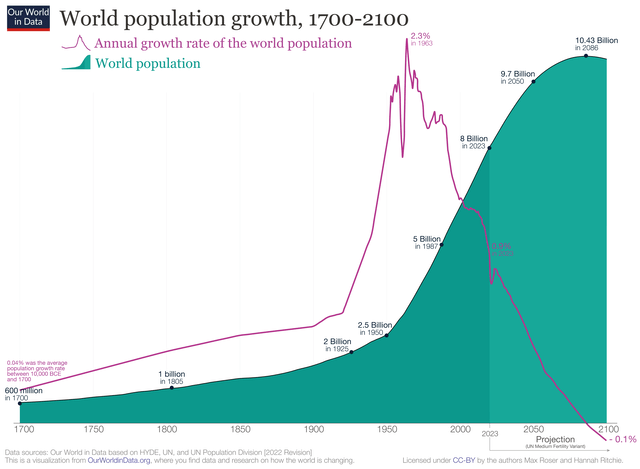

As far back into history as we can see, the global population of humans has steadily grown, albeit with some brief interruptions due to plagues, wars, and natural disasters.

Never before in history has the human population been so insulated and protected from the deadly effects of these extrinsic factors.

And yet, our global population is nearing its peak.

Some countries, like China, Japan, South Korea, Italy, Greece, and Portugal, are already seeing their populations shrink. Many other developed nations are within a generation of peak population and would already be reaching their peaks if not for immigration. The whole world is currently expected to reach peak human population by around 2080.

The human population is in the process of topping, so to speak. The long era of human population growth, especially the century of rapid growth in the 1900s, is coming to an end.

It is being replaced by a period of rapidly decelerating growth that is expected to last the next several decades.

After sometime between 2055 and 2080, the global human population is widely expected to decline indefinitely.

This tectonic shift in human history will have profound impacts on the economy and investment landscape.

Here are some outcomes we envision from the current era of peaking population (and eventually depopulation):

The labor force will stagnate and then shrink.

Aggregate consumption will stagnate.

Homes in average locations will see values stagnate or fall.

Government old-age pension systems will strain under the weight of a diminishing worker-to-beneficiary ratio.

Innovation and productivity growth will likely slow down considerably, as there will simply be fewer entrepreneurial young people and less aggregate consumption to make long-term investments in new technologies worthwhile.

Healthcare systems will strain from the combination of high demand and labor shortages.

AI and automation will increasingly fill gaps in the labor force, especially among knowledge-based workers.

Economic growth will become increasingly reliant on attracting and integrating immigrants into a nation's workforce, especially in areas where AI and automation cannot easily replace human labor.

In our view, all of the above combines to result in a very long-term, gradual, secular headwind to both GDP growth and inflation.

You can observe that from the cases of Japan, Italy, Portugal, Greece, and most recently China, which have all experienced anemic GDP growth and inflation after their respective populations peaked.

The "Population Bomb," as a doomsday-predicting book from 1968 once called runaway population growth, has been defused.

Let's dive deeper into this topic and explore why slumping population growth or outright depopulation (depending on the particular country) should lead to a generally low rate of economic growth and inflation.

Peak Humanity Is In Sight

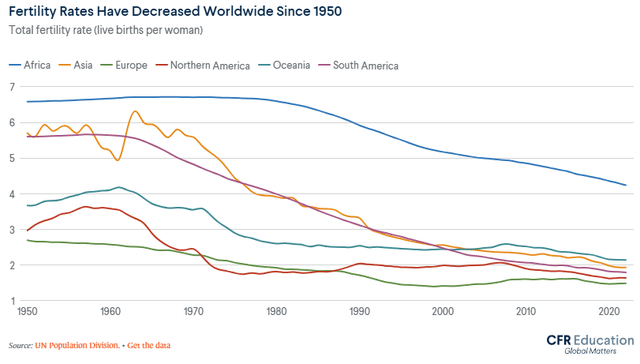

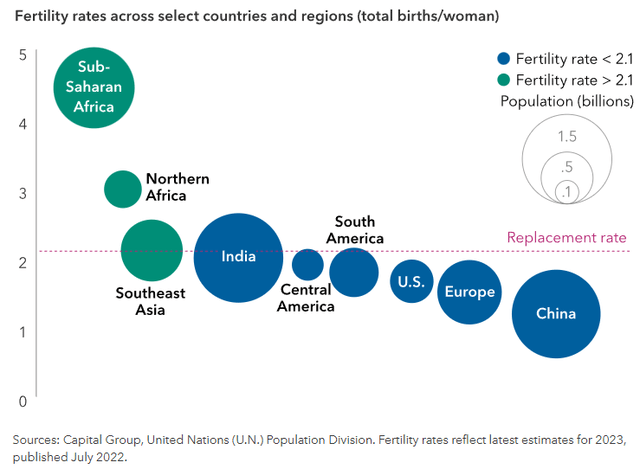

We won't get into the reasons why the birth rate has declined so much in the last half-century or so, but suffice it to say: it has. In most parts of the world, especially the developed world, the birth rate is under the replacement rate of about 2 kids per couple.

Sustain that situation long enough and eventually a nation's native-born population (excluding immigrants) will begin to shrink. That is happening today all over the developed world as well as several developing nations like China, India, and parts of Latin America.

And the way the trends are going, it will someday be happening almost everywhere in the world.

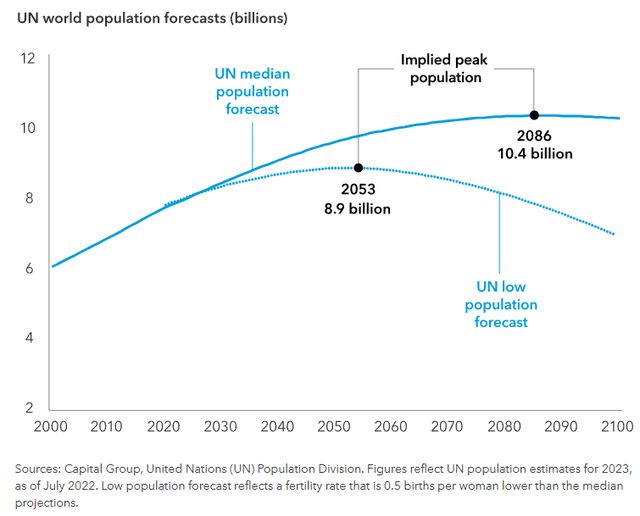

In fact, the United Nations recently revised its global population forecast again. The organization once foresaw the human population continuing to grow right up through the end of this century. Then, in the face of falling birth rates, they revised that down to a peak in the 2080s. And most recently, after COVID-19 and continued drops in fertility, they revised it down again to a projected peak population of about 9 billion people in the mid-2050s:

Note that a peak population of about 8.9 billion people 30-ish years from now would represent growth of only about 8.5% from the currently estimated 8.2 billion people on Earth.

The problem is that growth in the economy and standards of living are largely fueled by an ever-growing population of humans who can be consumers, workers, and innovators in that economy.

To quote Capital Group:

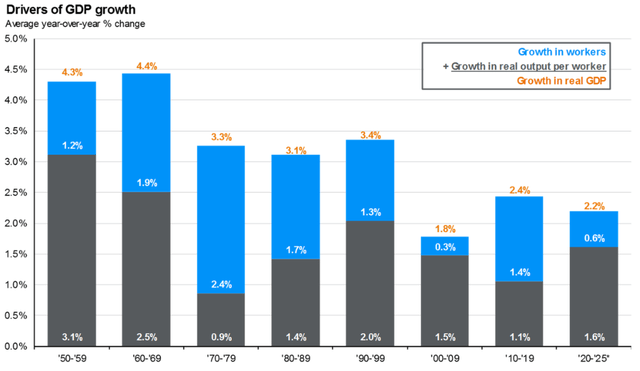

Put simply, the long-run economic growth rate of a country depends heavily on population growth, with the other piece of the puzzle being productivity, which measures worker efficiency. That is, if you have population growing at 2% and productivity at about 1%, a country’s gross domestic product is about 3%.

The economy is basically the combination of labor, capital, and productivity.

Slower population growth, and ultimately a declining population, has a direct impact on aggregate consumption, because all humans are consumers. Fewer humans means less spending, all else being equal.

It also has a direct impact on the size of the labor force. Fewer workers, all else being equal, means less production.

So, on both the consumption and production sides of the economy, slower or negative population growth acts as a severe headwind to the economy.

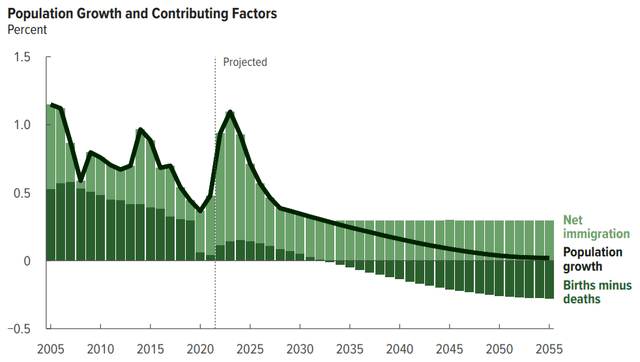

That makes it concerning to see the Congressional Budget Office's most recent demographic outlook for the next 30 years, showing population growth continuing to steadily decline through 2055.

Notice the dark green bars, representing births minus deaths, steadily trending down over the last 20 years. That will not stop when they reach zero. They will keep moving down into negative territory. The CBO currently forecasts the births-minus-deaths number to turn negative by 2032 or 2033.

Notice also that the only thing keeping US population growth positive after 2032 or 2033 is net immigration, which the CBO assumes will remain steady thereafter.

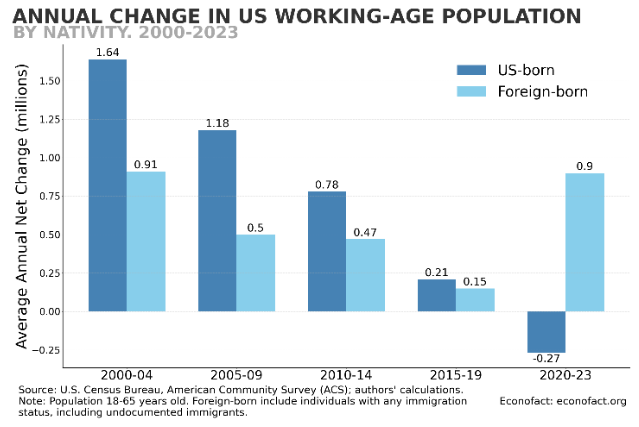

Unfortunately, the demographic situation is even more dire than the above chart makes it seem. While births-minus-deaths has not yet turned negative in the US, the native-born working-age population has already dipped into contractionary territory.

If not for net immigration, the working-age population in the US would already be on the decline. The native-born American population is aging quickly, with the last few years of the large Baby Boomer generation soon to reach age 65.

To quote the Economic Policy Institute:

Without immigration, the prime-age workforce (between the ages of 25 and 54) would have seen essentially no growth at all in the past quarter century, dramatically constricting the ability to grow our economy and staff key industries.

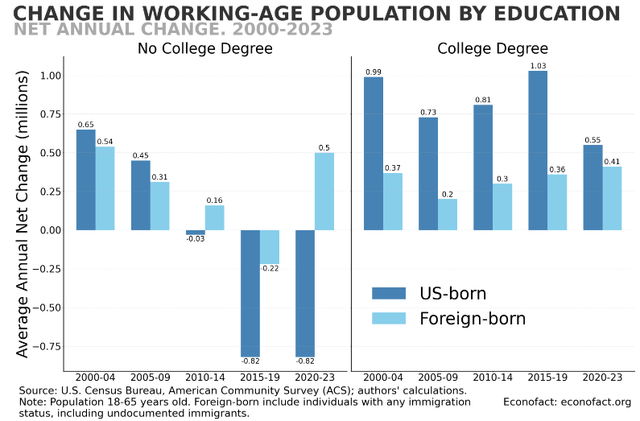

Interestingly, it is the low-education (no college degree) part of the labor force that has experienced the sharpest decline in native-born working-age people over the last decade, whereas the college-educated working-age population has continued to grow among both the native-born and foreign-born.

One major reason for this was the systemic push toward college education over the last half-century or so. More and more high-schoolers have gone on to college, because that's what they were told would lead to the best opportunities in life.

But by the mid-2010s, as you can see above, that lead to a decline in the non-college educated native-born working-age population.

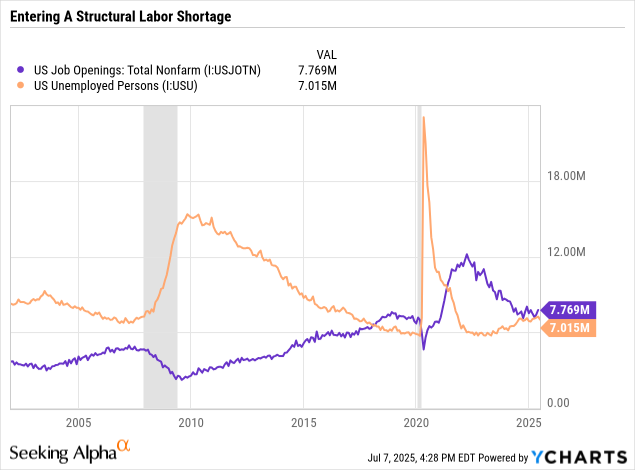

Interestingly, it is during the late-2010s that we saw the multi-decade US labor surplus (due primarily to the Baby Boomers) flip into a labor shortage. You can see this flip by comparing job openings to total unemployment:

From the 1980s (when Boomers were entering the workforce) to the mid-2010s (when they began retiring en masse), the US had a structural labor surplus that kept the unemployed population larger than the total number of job openings. Jobs were relatively hard to get during this period.

Then in the late-2010s, that situation flipped. Since about 2017 (outside of the idiosyncratic COVID pandemic), job openings have remained consistently higher than the total number of unemployed people.

The area where this growing labor shortage was felt most acutely was the blue-collar or working-class part of the workforce.

In early 2021, as the economy was reopening, The Conference Board pointed out the absolutely huge amount of blue collar and manual services job openings across the country.

One of the last generations of native-born Americans who weren't pushed toward college when they were in high school were retiring en masse, creating huge numbers of job openings suitable for non-college-educated workers.

That played a huge role in the surge of immigration, especially of unauthorized immigrants who tend to be less educated, witnessed after the pandemic.

Immigrants go where the economic opportunities are. That has been true throughout human history. It is not a new phenomenon.

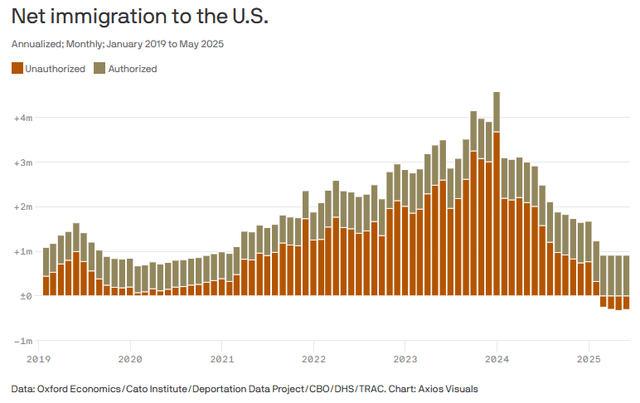

Notice, however, that net unauthorized immigration has now turned negative as the Trump administration has begun their promised deportation program. While this is a hotly debated political topic, we would simply assert that the economic impact is a net negative.

Raiding worksites (farms, hotels, restaurants, nursing homes, meat processing facilities, construction sites, Home Depot parking lots, etc.) to arrest unauthorized workers will inevitably exacerbate the labor shortage in key American industries.

To quote an article from Econofact:

The likely result will be a slowdown in growth of the economy, especially for the sectors depending on immigrants: agriculture, construction, leisure and hospitality, and personal care. Those sectors will likely experience some lower efficiency of their services, wage increases and price increases, as these services become more costly. Additionally, recent research from the U.S. and elsewhere finds that when labor markets are tight and firms have a hard time finding workers, as it has been the case in the US in the last 2 years, the opening to new arrivals through immigration helps firm growth and increases firm formation, with no negative impact on wages of natives.

Likewise, in a July 2025 report titled "Immigration Policy and Its Macroeconomic Effects in the Second Trump Administration," economists from the American Enterprise Institute and Brookings Institution estimate that net immigration into the US (including authorized and unauthorized) in 2025 will be between -525,000 and 115,000. They project net immigration numbers to be even lower in 2026, almost certainly ending up in the negatives.

The researchers foresee this having a 0.3-0.4 point drag on GDP growth this year and slightly more next year.

To quote the report:

Slowing immigration will put significant downward pressure on growth in the labor force and employment. Potential employment growth, meaning employment growth when the labor market is operating sustainably at “full employment,” could be between 10,000 and 40,000 jobs a month in the second half of 2025 (down from 140,000 to 180,000 in 2024), and potential job growth could turn negative in the second half of Trump’s term.

The cumulative effect of steadily removing foreign-born workers from the labor force is a reduction in GDP and jobs growth.

Rather than pushing up the wages of native-born workers, a shortage of workers due to negative net immigration is more likely simply to stunt economic growth, destroy jobs, and prevent other jobs from being created.

Multiple studies done on the deportation program ("Secure Communities") during the Obama presidency (for example: this one and this one) found that deportations paradoxically had a negative effect on American-born workers due to lost jobs and lower wages.

To quote the second study:

Research shows that mass deportation would negatively impact the American economy and people in a number of ways... Jobs for American workers would decline. Instead of native-born Americans having new work opportunities opened up for them and replacing deported unauthorized workers, research shows that overall employment would fall for the native-born... Instead of more competition for workers driving up wages, for most Americans wages would face downward pressure as jobs were lost and the economy shrinks.

To circle back to our previous point: On both the consumption and production sides of the economy, slower or negative population growth acts as a severe headwind to the economy.

The economy can be basically thought of as a function of the number of workers and those workers' labor productivity.

Over time, as you can see, both the workforce and labor productivity have been trending down in terms of growth rates.

With net the native-born working-age population and immigrant workforce both facing strong headwinds to growth right now, we don't think the US workforce has much room to grow.

That will almost certainly mean lower GDP growth, which often translates into less investment into productivity-enhancing technologies by businesses.

AI To The Rescue?

It is around this point when most writers on this subject will pivot to a hopeful outlook that artificial intelligence and other labor-saving technologies will come to the rescue and save us from our structural labor shortage.

But here's the problem: AI looks poised to primarily eliminate white-collar jobs. Several prominent CEOs have espoused the view that AI will significantly reduce white-collar jobs, with the CEO of Ford (F) claiming that AI will eventually eliminate half of all white-collar workers in the US.

These types of jobs still enjoy a decent inflow of workers from the native-born and legal/authorized immigration channels. This isn't the area where the US economy has the greatest labor shortage. Rather, we may even have a surplus of certain white-collar workers in this country going forward.

But the area where the US has the greatest labor shortage is in blue-collar, non-college-educated types of jobs.

Construction, food services, hospitality, meat processing, various trades, automotive maintenance & repair, and agriculture are some of the most consistently cited industries of persistent labor shortages today. (See here, here, here, here, and here.) They also feature some of the highest rates of foreign-born workers.

While AI does look poised to reduce the labor force needs in various white-collar fields, labor-saving technologies for the blue-collar types of jobs listed above appear to be a long way off.

Conclusion

All of the above leads to our conclusion that in the coming years and beyond, US economic growth is likely to decline.

We've seen this in various economic projections, including from the Federal Reserve. Real GDP growth will face strong headwinds from a sharp reduction in the growth of the US labor force and population. And this is to say nothing about the growth-stunting effects of tariffs on top of that!

Now consider that inflation appears to be durably low, as we argued in our most recent US inflation report.

Consider also our observation from a recent Market Update that long-term interest rates are basically a function of nominal GDP growth -- real GDP growth plus inflation.

The line of reasoning above leads us to believe that nominal GDP growth should decline over the next few years.

If that forecast proves accurate, then long-term interest rates should likewise trend downward.

All else being equal, such an environment of low-but-positive economic growth, low inflation, and falling interest rates is ideal for the performance of REITs.

Finally, please note that we have exceptionally posted this article without a paywall. If you found it valuable, consider joining High Yield Landlord for a 2-week free trial.

You will also gain immediate access to my entire REIT portfolio, real-time trade alerts, exclusive REIT CEO interviews, and much more. We are the largest and highest-rated REIT investment newsletter online, with over 2,000 paid members and more than 500 five-star reviews.

We spend thousands of hours and over $100,000 per year researching the market for the most profitable investment opportunities, and we share the results with you at a tiny fraction of the cost.

Get started today - the first 2 weeks are on us:

Analyst's Disclosure: I/we have a beneficial long position in the shares of all companies held in the CORE PORTFOLIO, RETIREMENT PORTFOLIO, and INTERNATIONAL PORTFOLIO either through stock ownership, options, or other derivatives. High Yield Landlord® ('HYL') is managed by Leonberg Research, a subsidiary of Leonberg Capital. All rights are reserved. No recommendation or advice is being given as to whether any investment is suitable for a particular investor. The newsletter is impersonal and subscribers/readers should not make any investment decision without conducting their own due diligence, and consulting their financial advisor about their specific situation. The information is obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but its accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The opinions expressed are those of the publisher and are subject to change without notice. We are a team of five analysts, each contributing distinct perspectives. Nonetheless, Jussi Askola, the leader of the service, is responsible for making the final investment decisions and overseeing the portfolio. We do not always agree with each other and an investment by Jussi should not be taken as an endorsement by other authors. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Our portfolio performance data is provided by Interactive Brokers and believed to be accurate but its accuracy has not been audited and cannot be guaranteed. Our portfolio may not be perfectly comparable to the relevant index. It is more concentrated and may at times use margin and/or invest in companies that are not typically included in REIT indexes. Finally, High Yield Landlord is not a licensed securities dealer, broker, US investment adviser, or investment bank. We simply share research on the REIT sector.

Thanks for your thorough analysis. There’s a lot to unpack. I’m not sure how this will play out, but there’s something sweet about it. REITs are likely to be in a strong position for the long haul.