What Austin Bought And Sold In September 2025

This is the next installment in our monthly series on the portfolio of our macro analyst, Austin Rogers. Please note that our main focus will remain on the HYL Portfolios, but since many of you have expressed interest in knowing how Austin manages his portfolio, we are posting this to give you extra value.

As I write this, I just returned from a month-long stay in the Rocky Mountains.

The first part of the trip was with my wife and her parents, the last part with my family, and for a quiet week in the middle, I was by myself. That week offered the opportunity for lots of solitary hiking, reading, and thinking. (An introvert’s dream come true.)

I’ve been to Colorado nine years in a row, drawn by the otherworldly beauty of its evergreen forests, alpine lakes, snowmelt creeks, and color-changing aspen trees. Being there is like taking a sabbatical. There’s something extraordinarily rejuvenating and restorative about unplugging and giving the mind extended time to wander undistracted as the body wanders down a trail. I always leave the Rockies with a renewed outlook on life and epiphanies that can only be acquired many miles into the pines.

It was on a trip to the Rockies during the summer of 2020 that I decided to quit my job as a real estate agent to focus on financial writing.

And several years ago (two or three, I can’t remember), I came away from a hiking trip with the epiphany that I should work smarter, not harder -- i.e. writer fewer but higher quality articles.

This year, I came away with several personal epiphanies as well as some Big Picture thoughts on the economy. I’ll spare you on the personal epiphanies, but here are some thoughts on macro stuff:

1. The K-shaped economy will have negative consequences

I’ve written recently about the K-shaped economy, which to my mind represents the vast and widening gulf between the Affluent class and the Paycheck-to-Paycheck class.

Now, I don’t want to get into politics here at all, but it might be worth noting that I am a classical liberal and do not disapprove of inequality per se. That is, there is no moral intuition within me that says it is wrong for some people to be rich and others poor.

But from an economic standpoint, I think the widening gulf between rich and poor in the US, as well as the increasing reliance on the consumption of the Affluent to drive growth, has certain consequences that investors shouldn’t ignore.

What do the housing market, Las Vegas, and Disneyworld all have in common? They have all become unaffordable to the vast majority of Americans. And yet, they keep getting more and more expensive, because the wealth and income of the Affluent class keeps rising, which allows them to further bid up prices.

I noticed this when visiting the ritzy, ultra-luxury ski resort town of Vail, Colorado. Even in September, an off-season month, restaurants were packed, the Sunday farmers market was as busy as ever, and parking was full at nearby hiking trails.

And yet, plenty of recent news stories highlight the mounting financial struggles of the Paycheck-to-Paycheck class, including auto loan and credit card defaults, dismal consumer confidence among low- to moderate-income households, and a rising share of the population that doesn’t even have $400 in savings.

Moreover, an economy increasingly reliant on the consumption and capital of the rich is a narrow and fragile one. A big downturn in the stock market or housing market, or a wave of white-collar layoffs, could cause disproportionately large and destructive ripples through the economy.

I think there will be a political backlash against the Affluent that will probably include higher tax rates (targeted at the wealthy) and government interventions intended to help the Paycheck-to-Paycheck class.

Whether these potential future measures reverse the tides of inequality remains to be seen.

2. The AI boom increasingly resembles the Dot Com boom in some ways

Allow me to shamelessly plug my weekly article, “Say No To FOMO And Stick To Your Long-Term Strategy.”

(The article got dismally few page views largely because the editors published it on Sunday instead of my normal Saturday morning time. It got held up by their AI-writing filters, which three times now have rendered false positives about my writing. I’ve never used AI-generated text in my articles, but some words or phrases I use keep making the AI-writing filter think otherwise. Maybe I should take it as a compliment?)

In that article, I discuss data from a report put out by Michael Cembalest of JP Morgan as well as a piece in the Wall Street Journal, both covering the mounting evidence of a bubble in the AI space.

To quote a portion of the WSJ piece that I cited in the article:

This week, consultants at Bain & Co. estimated the wave of AI infrastructure spending will require $2 trillion in annual AI revenue by 2030. By comparison, that is more than the combined 2024 revenue of Amazon, Apple, Alphabet, Microsoft, Meta and Nvidia, and more than five times the size of the entire global subscription software market.

Okay, so the amount of AI infrastructure spending (which continues to grow, by the way) currently underway would require revenues in 2030 equivalent to five times the current global SaaS market. That’s about 44x total AI revenue from 2024. By my guesstimate of the 2025 AIaaS (AI as a service) market, AI infrastructure will require about 25-30x this year’s total AI revenue to be profitable.

This is increasingly reminiscent of the overbuilding and overinvestment that occurred during the Dot Com bubble, which was another period of euphoria over a revolutionary new technology.

Everyone knew the Internet was revolutionary, but investment into the Internet economy grew way faster than profitable and implementable uses of it did.

It took decades for the Internet to transform the economy, but in the late 1990s, Internet-related companies were investing in capex as if this transformation would happen in the span of just a few years.

To quote Lisa Dolan from an article on Medium:

The late 1990s saw a massive investment in fiber optic infrastructure, driven by the anticipation of exponential growth in internet traffic. Companies laid extensive networks of fiber optic cables, leading to significant overcapacity. By 2001, it was estimated that only 5% of the installed fiber-optic capacity was in use, resulting in a telecom crash that caused substantial financial losses and bankruptcies within the industry.

Investors vastly overestimated the amount of Internet bandwidth that would be needed in the next few years and overbuilt accordingly. It wasn’t until the late 2000s that video streaming services like Netflix (NFLX) finally utilized all this excess capacity.

Do these paragraphs, published in August 2002 in an article titled “The Great Telecom Implosion” in The American Prospect, sound familiar?

When it first broke into public view, the Internet seemed like an economic as well as a technological miracle. As consumers, Americans came to expect that the information and services they found online would be free, while as investors they believed that the Net would generate billions of dollars in profits. A miracle is exactly what it would have taken to realize both those expectations.

... By 2000, however, companies began to realize that there simply wasn’t enough business to go around, and they raced “to gain market share” in a burst of “hypercompetition” and “vicious price wars” that drove down revenues.

I’d conjecture that most consumers of AI think it is a really cool technology that, like Internet search engines, they will never have to pay for.

I would also argue that a lot of the recent announcements of massive infrastructure investments have been catalyzed by “hypercompetition.”

Here’s another snippet of the article:

To inflate their profits, some counted operating expenses as capital investment.

I’d argue that this is exactly what data center REITs like Equinix (EQIX) and, to a lesser extent, Digital Realty (DLR) and Iron Mountain (IRM), do. They classify hardware upgrades (that are essential to remain competitive in a world where new, state-of-the-art data center chips come out every six months and have useful lives of 2-3 years) as growth capex rather than maintenance capex. This allows them to exclude this spending from AFFO per share and thus inflate their bottom line.

And here’s one more snippet:

Or two companies with excess capacity would sell each other the right to use a share of each other’s networks. In such a swap, for example, each firm might book $150 million in revenue from the transaction when, in fact, there was no real revenue at all. Not only did such a swap allow each firm to deceive investors about its business, it also created the impression that the industry as a whole was $300 million larger than it actually was.

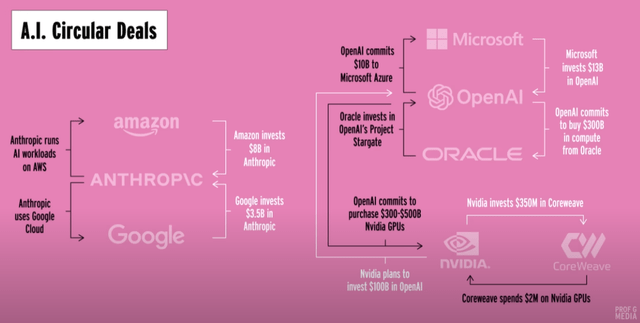

I discussed a similar form of circular spending within the AI-tech space in my “Say No To FOMO” article linked above.

Here’s a helpful illustration I recently came across:

In the late 1990s, during the massive and rapid buildout of Internet infrastructure, the tech hardware company Cisco (CSCO) engaged in a form of seller financing in which it lent money to telecom companies who would then buy Cisco’s “picks and shovels.”

Similarly, today we see hyperscalers, AI SaaS companies, and semiconductor businesses like Nvidia (NVDA) engaged in a big circular flow of spending and investment -- all premised on the notion that within a few years, demand for AI software products from outside the AI-tech space will be so great as to more than justify this circular investment.

To be fair, though, one big difference between the Internet infrastructure investment boom and today’s AI infrastructure investment boom is that most of the former was funded by debt, whereas most of the latter (so far) has been funded via the massive cash flows of the hyperscalers.

That means that a potential bursting of the AI infrastructure bubble would look different today than the bursting of the Dot Com bubble looked in the early 2000s.

Nevertheless, unless we see a massive ramp-up in AI SaaS revenue from outside the tech space in the very near future, it does look like history will end up largely repeating.